I’m going to break a few rules today. I’m going to take you on a guided tour of an engineer’s thought process. Just in case you know an engineer and realize just how easily we get distracted, we’ll keep this very focused with no detours allowed.

My particular brand of engineering is electrical but except for the problem I’ve selected, it really makes very little difference in the way we think.

To give everyone has an equal view I need to explain some basic elements of electricity. Electricity is based on a flow of electrons. To turn a motor, light a light or heat your oven, there has to be a way for the electrons to get in and a way for them to get out.

When some one talks about a short circuit, it means those tricky little electrons have found an alternate path to avoid doing the work you intended them to. In most cases this results in too many of them trying to avoid work and is usually accompanied by a lots of heat, smoke or even fire.

An open circuit is just the opposite. Now the electrons have no path to do the work you intended. Your light switch does just that. When you flip it to the “Off” position, it opens the circuit, electrons stop flowing, and your light goes off.

We need one more character for this tour. A relay is another version of a switch. When power is applied to the relay, it activates another path for the electrons. This path is typically described as the relay contacts. Relays are useful because they allow small switches to control very high current applications.

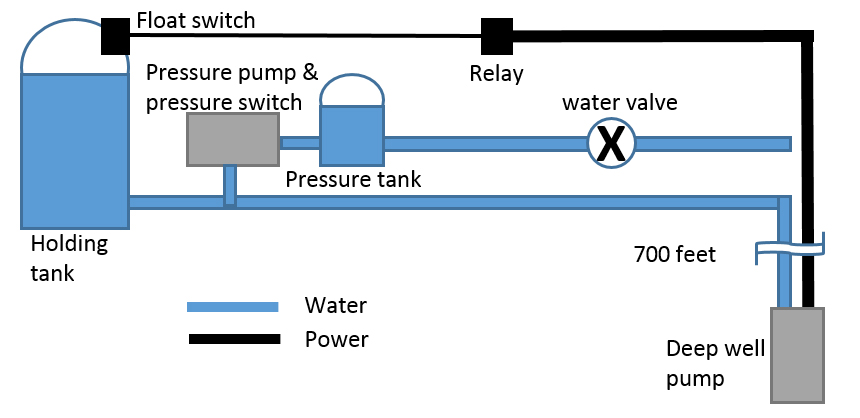

There’s the basics, now to introduce the problem. Living in the country my water comes from a well. My water system is a little more complicated than normal because my well is 700 feet deep. This results in a deep water pump, a 1200 gallon holding tank, a pressure pump and a 70 gallon pressure tank. When it works, it works well. When it doesn’t, let’s just say that getting it fixed is a high priority.

Water System

When my wife comes to me and says we have no water, my mind immediately jumps into high gear analyzing the possible failures, what my options are for immediate water and how much this will cost. On second thought, my wife reads this blog so I’d better be truthful. After my initial “Huh”, I ask her what happened and what isn’t happening. Being a little more truthful than I should, I’m really no longer listening to her.

As an engineer I’m driven to solve problems and it’s not the prospect of no water or the concerned wife that drives me. This represents a challenge. I’m already reviewing the system in my head for failure points. Once I have that firmly in mind I go outside to the well house for more data.

Float switch showing full tank

In this case data consists of the position of the float valve in my holding tank, is my pressure pump running and the pressure on my pressure tank. I can’t tell anything about the lower pump because at 700 feet down, I can’t hear it. My holding tank is opaque so I can only see that the float position is low enough that the deep well switch should be on.

My pressure pump is running but the pressure in the small tank is not rising. I have three possibilities here, no water in my holding tank suggesting a failure in that portion of the system, a break in the water line causing all my water to run out or a failure of the pressure pump and it can no longer build up pressure. A failure of the pressure pump would not be consistent with the holding tank being low. I can rule that out right away.

I shut off the water valve to the outside, if I have a broken line my pressure will start going up rapidly. That doesn’t happen. I’m now fairly sure that I have an empty holding tank and the problem is with my lower pump system. I shut off the pressure pump, it can’t do its job until I have water in my holding tank.

I talked about relays earlier and you can see from my diagram that my deep pump is driven by a relay. Fortunately I can see that my relay is activated. That means the float valve switch is working. I’m now down to two possible failures, the deep pump or the relay. Those of you that know electronics are already jumping up and down with a third answer, the wiring to the pump. You’re right of course but a break at any point past the entry to the well means pulling the pump. The cost is the same, the effort is the same.

Using my voltmeter I finally took a measurement. To my immense relief, I have power on one side of the contacts but not the other, even though the relay is fully engaged. I disconnect power, bypass the relay, reconnect power and hear my deep pump starting up. I was correct, it was a bad relay.

The culprit, a defective relay

I should also mention that after having to manually switch the deep pump on and off for two days while waiting on a relay, I bought two spare relays. I let my wife know that the outage was temporary, replaced the relay and waited on the holding tank to fill back up before reconnecting the pressure pump.

Now let’s go back to the start of this and look at the process I followed. I reviewed the system to understand where the failure points were. I worked backwards from the symptoms (no water, pressure pump running constantly…) coming up with theories for the failure at each point. I then devised and executed a test for each theory. When the final test (bypassing the relay) worked, I knew I had isolated the failure. From there I only had to replace the faulty component and verify its failure had not caused any other problems. This is a deeply ingrained process and is how I approach all my problems.

In writing this, I was careful to pick an example that would show off my skill in troubleshooting but think about this, my poor wife has to endure this for each and every problem she brings to me. When she has a problem, she wants to tell me all the symptoms and what she thinks went wrong. I’ve learned to stay quiet and listen (I try) but until those symptoms come up as data to prove or disprove a theory, I regard them as distracting noise, likely to cause me to miss a step in my process.

Pity the poor person married to an engineer.

© 2013 – 2019, Byron Seastrunk. All rights reserved.

I might not want to be married to an engineer but it sure is nice to have one in the family…..they know how to fix everything!