In his lectures on rhetoric, Professor Michael Drout said write what your audience needs to hear, not what you want to say. Each time he said that I nodded my head in agreement. This concept was important enough that he repeated it several times at various points in his lecture. About the third time this principle came up, I realized with a start that I had already learned this lesson. When I first learned this lesson it had been presented to me as a hardware design principle. I was fortunate that the person teaching me was an engineer that also happened to be the company vice-president.

The lesson started when I was given design lead on an important program. I was ecstatic. This was to be the first major design from our site and would mark the transition of engineering capability from headquarters to our site. It was also my first major design. No one has ever accused engineers of having small egos and in retrospect I probably should have realized that my three man engineering team was not expected to succeed.

In my opinion, our company’s previous products were very limited in their choice of microprocessor and control options. I intended to show everyone what could be done when it was properly designed (ego again, no lack here).

The stakes were high enough that the Vice Presidents from both sites were going to be monitoring my progress. Rather than feeling pressure I felt this was my big chance to show what I could do. I was still naive enough to believe that everyone was focused on the success of the company and both VPs wanted to see me succeed.

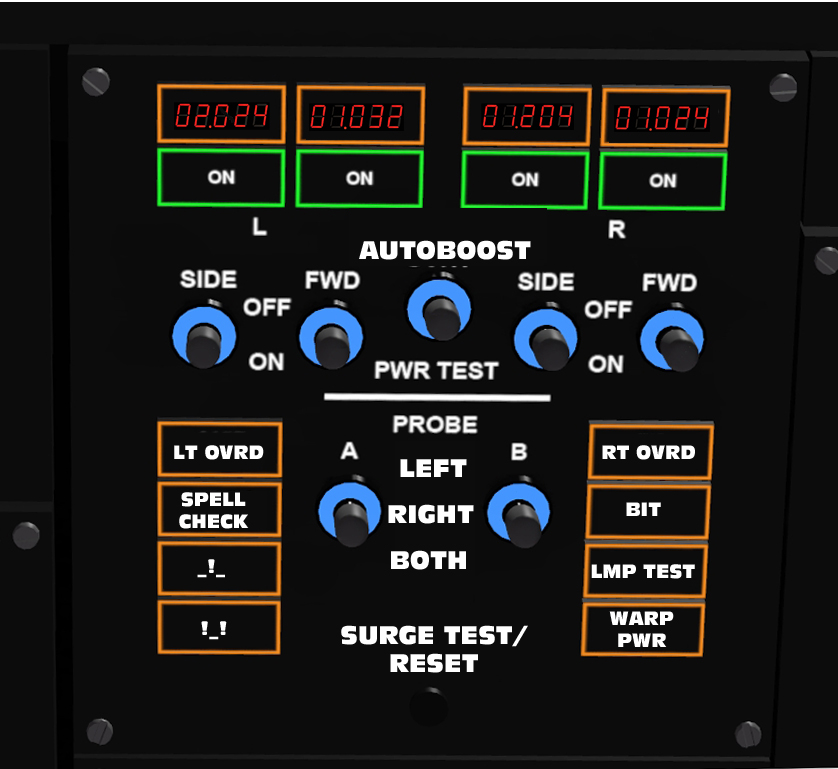

Aside from some simple functions, my design only had to be rugged and easy to use. It was being used in an aircraft with the pilot selecting a few options and then ignoring it. This was not the basis for a showcase design. Undaunted, I did diagrams of all the functions. I created options for all the functions. At this point my microprocessor was barely taxed so I continued adding functions.

Once I had decided on the functions, I started adding controls for each function and option. I was limited by the size of my front panel but by making the switches slightly smaller and using slightly smaller displays, I managed to get everything on the front panel.

It was beautiful. Nobody in the market had half the options my box had. Of course to get there, a few of my switches served dual functions but those were clearly marked. I was ready for my first design review. I was going to impress everyone.

The VP of my site, having been an engineer himself, had a very good idea what was happening in my mind. He set up a private review of my design and listened carefully to my explanation of all the modes. He looked at the artwork of my front panel and asked me if I thought it was too complex. How long would it take to train someone to use it? Would they really remember that the mode select switch doubled as a type select switch when the display showed a decimal point?

My wife would be the first to tell you that what I consider easy to use seldom is easy to use. After listening to me explain all the modes and the options, he knew that I was in love with the complexity of my design and had forgotten the user. Logic would never win out with me.

I can only hope that if I’m ever presented with a similar situation I handle it as well as he did. He praised me for the design and told me he wanted it to look very, very simple, a few toggle switches and a big rotary knob in the middle. He explained this was the only way corporate would not view it as a competition between the sites. We were to be the low cost, low complexity alternative.

I argued about loss of options, loss of fidelity, loss of pride but he had given me a logical argument that had no counter. I designed the box the way he wanted.

It was ugly, no displays, three toggle switches and a big rotary switch in the middle. For the next five years, every time a customer came in, they had nothing but praise for my design. They loved the simplicity of controls and especially loved being able to turn the knob where they wanted without even having to look at the controls. My VP always gave me full credit for the design, he never said I told you so.

You only have to look at all the appliances that never have their clock set properly to realize that engineers love their technology more than their customers. Does my microwave really need to know what time it is? Some engineer couldn’t stand the thought of those displays not working when the microwave wasn’t in use so I have one more clock to set when power goes out.

As I watch the transition from personal computer to tablet, I have to wonder if I’m not seeing this same lesson being presented in a grand scale. We were being presented with software so difficult to use it took experts to set up. Each version required faster and more complex hardware. We ordinary mortals seldom used more than 10% of the functions in these packages.

Some days I use my tablet far more than my PC. It’s a powerful lesson…

© 2013 – 2019, Byron Seastrunk. All rights reserved.

Excellent post, we are all guilty of self induced scope creep. The VP seems to know his stuff and respects his personnel. Imagine all the kicks in the head he experienced along the way to learn those lessons. Before retirement I always aimed to have the best people working with me. My goal was to me the dumbest person in the room.

Probably a lesson all of us should learn !