Tariffs are a tax nations charge on imported or exported goods. The importer always pays the tax, and the money always goes straight into the pockets of the country imposing the tariff. But don’t be fooled—while the importer technically pays the tax, the cost always gets passed down to you, the consumer. The importer treats the tariff as an additional cost, adds his profit and overhead on top, and hands you the final bill.

Let’s break it down. A Nakiri knife is a specialized knife for chopping vegetables. Japan sells a stainless steel version for $10. The U.S. slaps on a 10% tariff, so now the importer pays $11. But you didn’t buy that knife directly from Japan. The importer isn’t just going to eat that extra cost—he marks it up before selling it to you. A typical markup is about 30%, meaning the Nakiri knife now costs you $14.30. That little 10% tariff just cost you an extra $1.30. And if your state charges sales tax, guess what? You’re paying even more—another ten or twenty cents just to cover the tariff.

Let’s break it down. A Nakiri knife is a specialized knife for chopping vegetables. Japan sells a stainless steel version for $10. The U.S. slaps on a 10% tariff, so now the importer pays $11. But you didn’t buy that knife directly from Japan. The importer isn’t just going to eat that extra cost—he marks it up before selling it to you. A typical markup is about 30%, meaning the Nakiri knife now costs you $14.30. That little 10% tariff just cost you an extra $1.30. And if your state charges sales tax, guess what? You’re paying even more—another ten or twenty cents just to cover the tariff.

Sure, the importer could choose not to pass the cost on to you. But let’s be real—why would he? He has to consider his profit margins. If the numbers don’t add up, he’ll stop importing these knives altogether, and suddenly, you won’t be able to buy them at all.

Export tariffs work the same way—except they’re usually used as retaliation or to boost local industries. The importer pays for the product and then gets hit with export tariffs on top of that. And once again, the government imposing the tariff rakes in the cash. The math doesn’t change. If Japan decides too many Nakiri knives are leaving the country and its citizens start complaining about a shortage, the government might slap a 10% tariff on exported knives.

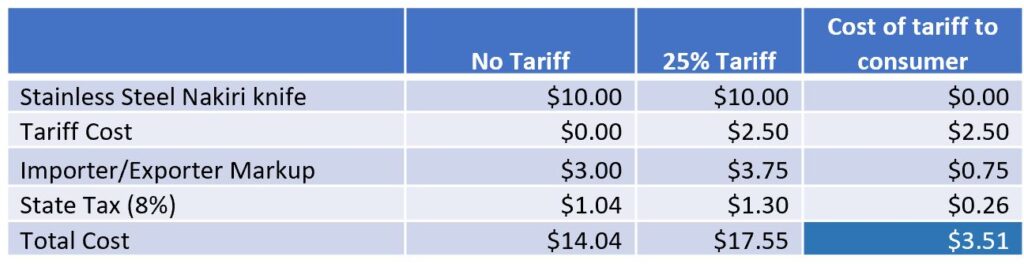

Now, let’s say you want to “protect” your local Nakiri knife industry. You impose a 25% tariff on imported Nakiri knives. The idea is that this will encourage domestic production. Sounds great, right? Well, here’s the problem: Nakiri knives require skilled labor, and the infrastructure to make them doesn’t exist overnight. For years, people will still have to rely on imports, meaning they’re paying even more.

As the domestic industry finally starts catching up, prices will “adjust” to market demand—meaning they’ll still be high. In fact, they’ll probably land just below the price of imports, because someone has to cover the cost of the new factories and equipment. We saw this happen when Trump slapped a 25% tariff on Canadian softwood. The price of toilet paper, which is mostly made from softwood, immediately jumped. Eight years later, it’s still ridiculously expensive. Every time I buy a pack, I wince.

Trump has claimed he could eliminate taxes altogether and just run the government on tariffs. Who needs the IRS, right? Sounds great until you realize what that actually means. No more deductions for child care, mortgages, or anything else. You’re no longer paying income tax, sure—but every time you buy anything, you’re paying way more than you were before. And guess what? If you’re rich, this system barely touches you. Sure, you pay a little extra, but most of your spending is on services, which aren’t affected. Meanwhile, working and middle-class Americans feel the full weight of these hidden taxes.

Trump has claimed he could eliminate taxes altogether and just run the government on tariffs. Who needs the IRS, right? Sounds great until you realize what that actually means. No more deductions for child care, mortgages, or anything else. You’re no longer paying income tax, sure—but every time you buy anything, you’re paying way more than you were before. And guess what? If you’re rich, this system barely touches you. Sure, you pay a little extra, but most of your spending is on services, which aren’t affected. Meanwhile, working and middle-class Americans feel the full weight of these hidden taxes.

Let’s follow the money.

Here’s our scenario: Japan sells a $10 Nakiri knife and look at what happens when the U.S. slaps a 25% tariff on it, well just because…

That 25% tariff doesn’t just increase the price by 25%. By the time you, the consumer, get hit with it, the total increase is $3.51.

You might not care about Japanese vegetable knives, but this logic applies to everything. Every time a tariff is imposed, you’re paying not just for the tariff itself, but for the importer’s markup on the tariff, plus taxes on the tariff. Oh, you noticed that? That’s why they call it a tariff instead of just an extra tax—so you don’t realize you’re being double-taxed.

Now, let’s say you’re filthy rich and you commission a one-of-a-kind, gold-plated, custom-engraved Nakiri knife. The base knife is imported from Japan for $17.55, and your artisan decks it out until the final price hits $300. The tariff barely makes a dent. Less than 1%. Forget a progressive tax system—tariffs are a tax on everyone who actually uses the product.

Sure, this is a simplified analysis. It doesn’t even get into price elasticity—when prices rise, fewer people use Nakiri knives and simply use a steak knife. And it ignores the fact that, as sales drop, Japanese artisans will retire, making their products even more expensive. Or that Japan might retaliate with its own tariffs. It also avoids discussing tariffs on component materials such as Aluminum.

Bottom line: You are always paying for tariffs. The government imposing them always gets the money. So is it really a surprise that Trump loves them? And do you really think he’s going to replace income tax or use tariffs to lower your tax burden?

© 2025, Byron Seastrunk. All rights reserved.