When I write about engineers, I naturally try to show us in the best light possible. Still, there’s no arguing that some of the things you cope with as a consumer of the products we design would have been avoided if a blind monkey were the designer. Why does this happen? I call it a failure to communicate.

When my wife points to these deeply flawed designs and demands, “what’s up with that pile of horse manure?” I can’t admit the truth and say it was probably a failure to communicate on the part of the engineers. In defense of my fellow engineers, I usually say patents.

It’s a good diversion because my wife has already learned that nothing will put me on my soapbox faster than our current patent laws. It’s not that I don’t believe we need patents but I do believe the people granting the patents need to be as smart as the people applying for the patent. Prior art and intuitively obvious should have some meaning. Sorry, soapboxing.

It’s a good diversion because my wife has already learned that nothing will put me on my soapbox faster than our current patent laws. It’s not that I don’t believe we need patents but I do believe the people granting the patents need to be as smart as the people applying for the patent. Prior art and intuitively obvious should have some meaning. Sorry, soapboxing.

The thing is that sometimes bad designs are inevitable. I have yet to be on a project where the manager tells me to take all the time and budget I need. Sometimes we have to make compromises to get the product out the door before the manager decides to push you out of the door instead.

Many years ago, before I became the cynical old man I am now, I was faced with just such a situation. Essential to my design was a 24 position rotary switch. Adding 24 inputs to my board was going to cause severe crowding, so I selected a binary encoded switch. It was a good solution and only needed five inputs. Since I was also the programmer on this project, I was comfortable with creating the table I would need to decode the switch.

I got in touch with the switch vendor and found out that my switch was more of a concept than a real product. Fortunately, they could give me a prototypes. The real switches would be available by the time I was ready to go to production. In case you have any doubts, that should have been a red flag, with fireworks.

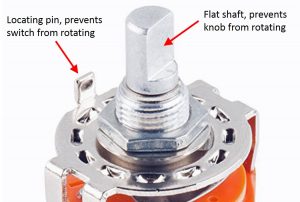

The prototypes were exactly what I wanted. We designed the faceplate and chassis so that “OFF” would be in the bottom left. The switch had a small locator pin that would lock it in position. That, along with the flat on the shaft of the switch, ensured the knob would always point to the right position. Perfect until the real switches came in.

There had been a design “enhancement” at the factory. With the locating pin and knob locked into position, “zero” was now in the upper right hand position. I could modify the mounting position of my switch, I could have some very expensive Plexiglas panels rebuilt or, and I hate to admit that it took me two days to realize this, I could use my table to redefine “OFF” as position 17 (0x10001 in binary). If my microprocessor read position 17, it did nothing. It was essentially off.

It made my software look a little funky but I was the programmer so it wasn’t a major issue. We went into production mostly on time and my manager never learned about my personal crisis. The truth is that selecting zero as the “OFF” position was an arbitrary decision that only mattered to me. At least that’s what I thought.

Moving down the road a few years, my box was a success but I was asked to remote the front panel. Given that I was allocated a whole two weeks for this effort, I used optocouplers to extend the front panel wiring by two feet. For those of you with no clue what I just said, think duct tape and baling wire. Ugly, but it worked and I made schedule.

A year later, deciding that my panel still took up too much room, our customer hired another company to modify their computer to control my box. The new company was either too arrogant or too constrained by budget to talk to my company about the task. If they had, we would have told them about the serial port on my box just for that purpose. After looking at the way I had remoted the front panel, they assumed this was the only way and added relays in place of the front panel switches (more baling wire and duct tape).

Months later, praise started filtering in for the way my box continued to operate when the computer went out but why had I selected such an odd mode. It took me a while to piece together all the details. If their computer went out (apparently, it frequently did), all the relays would open and my box would think the switch was in position zero. Because of the original confusion between the switch prototype and the final product, position zero was not off, it was an active setting for my box.

The default mode when their computer went out was nothing more than a series of, at the time, seemingly sound engineering decisions in order to meet deadlines. In this case, it took a vendor and two competing companies to botch the design. The resultant default mode I was being praised for was nothing more than a failure to communicate. It’s a true story. I may wonder how such bad designs made it out the door but I no longer criticize.

Oh yes, I also make sure I stay in close contact with anyone designing a prototype for me. Once burned and all that.

© 2017 – 2019, Byron Seastrunk. All rights reserved.