When I retired, my wife strongly suggested I put some of that newfound free time into cleaning rather than gaining another level in my current game. My trusty old vacuum cleaner, however, decided it wasn’t up to the increased workload and promptly broke a belt. Of course, it was so ancient that replacement parts were no longer available. This left me with no choice but to buy a new vacuum cleaner. Little did I know this purchase would open my eyes to just how poorly today’s manufacturers treat their customers.

After reading way too many reviews, I settled on a Eureka NEU181D. Fifteen minutes after unboxing, I had it assembled and was ready to tackle the dog-fur battlefield that was my living room. It’s labeled as a pet vacuum, so I started on the carpet my dogs had generously covered in hair. Apparently, they’d been shedding as if it was their full-time job. One pass with the vacuum, and I was impressed—the carpet looked brand new. But, of course, the honeymoon was short-lived. A few minutes later, the vacuum’s sound changed. Yup, the canister was full.

After reading way too many reviews, I settled on a Eureka NEU181D. Fifteen minutes after unboxing, I had it assembled and was ready to tackle the dog-fur battlefield that was my living room. It’s labeled as a pet vacuum, so I started on the carpet my dogs had generously covered in hair. Apparently, they’d been shedding as if it was their full-time job. One pass with the vacuum, and I was impressed—the carpet looked brand new. But, of course, the honeymoon was short-lived. A few minutes later, the vacuum’s sound changed. Yup, the canister was full.

Now, would reading the manual have helped? Sure. Did I bother? Nope. But I managed to empty the canister and reassemble it, feeling pretty confident. Then, as if on cue, my brand-new vacuum started blowing out dust like it was auditioning for a sandstorm scene in a movie. Adding to my woes, it was nowhere near as efficient. So, I stopped, double-checked that the canister was in right, and tried again.

Emphasis on *try*. The vacuum just refused to start. The lack of a click when I pressed the power button screamed “switch failure.” Naturally, I started disassembling the thing because who has the time for a warranty when your house is a fur minefield and the dogs are shedding like there’s no tomorrow? And let’s be real—I’m always more interested in *why* something failed than letting someone else fix it.

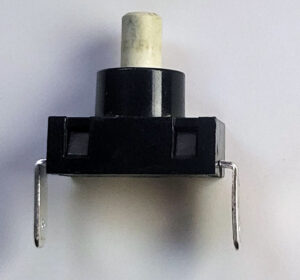

The culprit

With the vacuum now in pieces, I confirmed that, yes, the switch had crapped out. Replacement switches were available, but they’d take time to arrive, and time wasn’t on my side, thanks to my fluffy four-legged shedding machines. So, I took the only logical course of action: ripped out the original switch and wired in an external one. Problem solved—for now. But seriously, why did the switch fail after, what, 15 minutes of use?

Here’s where the facepalm moment came in. When I reassembled the canister earlier, I had put the filter in backward (cue the sarcastic applause). This allowed dust already in the filter to blast through the motor compartment. Remember how I said it was blowing dust everywhere? Yeah, about that. The power switch is one of those delicate press-on, press-off types, incredibly sensitive to dust. My brilliant filter mistake had let enough dust inside to clog the switch. A couple blasts of compressed air confirmed my suspicions—dust had killed the switch.

I was furious. Two dollars—that’s all it would have taken for a better switch or a sealed design to avoid this nonsense. So, when I left my review on Amazon, I gave it a glorious one-star rating. Is it a great vacuum? Sure, when it works. But Eureka cheaped out, choosing a bargain-basement switch over something that wouldn’t crap out after a minor mistake. Worse, after reading other reviews, I realized this wasn’t just a me problem. Tons of people were facing the same issue, many of whom went the warranty route only to be told it was *their* fault. Of course.

My fix

Yes, I admit I sped up the process with my backwards-filter blunder, but even if I had assembled everything perfectly, once that filter clogs up, dust will still get through and murder that switch. Eureka has known about this for years and hasn’t bothered to fix it. Too bad I couldn’t give that one-star rating directly to Eureka’s management.

I don’t know what trade-offs or testing went into designing this vacuum, but I do know they’re probably getting a hefty number of returns thanks to this switch issue. At this point, changing the design would cost tens of thousands of dollars, and you just *know* some pencil pusher in management decided it was more profitable to blame the customer when the switch failed than to fix the root problem. This is the kind of thing that gives engineers a bad name.

While I was riding my wave of cleaning enthusiasm, I also ordered a battery-powered scrubber. Yep, the peak of laziness, but it was on sale, and I was over scrubbing things manually. It came with a three-foot extension and a variety of cleaning pads—good for everything except maybe pots and pans.

Naturally, when I plugged it in to charge, nothing happened. The culprit? The USB-C connector on the provided cable was just a smidge shorter than a normal USB-C connector, meaning the electrical connection was hit-or-miss. Insert it with normal force, and no charge. Shove it in like you’re mad at it, and voilà, it charges.

Almost 1 millimeter difference

I’m convinced this was a tolerance issue, and I had rolled snake eyes. It wasn’t a huge deal for me since I almost never use the charger that comes with USB devices anyway. But let’s not overlook the irritating detail: shaving a penny off the cost by purchasing a slightly shorter connector ensured that 10 to 20 percent of these things would fail. Classic.

There’s no way this decision was made by an engineer. Engineers know better. From my personal experience across multiple projects, I’m certain procurement grabbed the lowest bid on a USB-C cable without understanding (or caring) why it was cheaper. And for what? To save a couple of pennies, they guaranteed a wave of bad reviews and high return rates.

Can I blame management for not fixing this? Not really. They probably don’t even know about the issue. My scrubber was a generic, privately branded product imported to be sold on Amazon. I don’t know who handles the warranties or returns, but I’m betting it was on sale due to the sheer number of returns. I gave it a three-star review—because, hey, it *technically* works once you figure out the charging quirk.

A few years ago, I wrote a post defending engineers’ decisions, touching on budgets, schedules, patents, and management interference. The bottom line? Yes, engineers make mistakes, sometimes spectacular ones. But before you go blaming the engineer for a lousy design, remember—plenty of other people influence the final product. It’s not always the engineer’s fault.

© 2024, Byron Seastrunk. All rights reserved.