I’m fairly sure it’s a conspiracy but since no one else is warning you, I feel that it’s my duty to warn you about the highly toxic nature of tomatoes. We’re all fortunate that tomatoes are becoming less toxic over time but their deadly nature cannot be denied. Of course, I don’t expect you to believe me, you want data.

100 percent of the people who ate tomatoes prior to 1910 are now dead. Think about that, 100 percent fatal. When you look at the fatality data, you can also see more and more people are surviving tomato toxicity. There are only two possible conclusions, either tomatoes are becoming less toxic with each growing season or humans are gradually becoming immune to the toxin. Admittedly, I don’t have enough data to make that determination.

Okay, we both know that in spite of my very accurate data, the conclusion is totally bogus. My data was carefully selected to support a theory that is obviously false. I can’t even take credit for the premise; it’s based on a semi-humorous article I ran across many years ago.

My real purpose was to show you the danger of blindly believing someone saying follow the data. I don’t know about you, but I’m sick and tired of people using questionable data to justify their actions. Don’t get me wrong, I fully support masking and vaccinations but enough is enough.

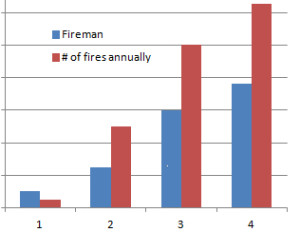

Obtaining good reliable data is always a problem. That’s the reason I suggested challenging the data if you find yourself in an argument with an engineer. A good engineer always questions the data. Interpreting it correctly is even more of a challenge. Consider the relationship between fires and firemen. Almost all large fires have firemen gathered around them. Pretty suspicious if you ask me.

When I see polls used to elicit opinions, I already know the respondents are predisposed to answer polls. That single trait makes them less representative of the general public. It stands to reason then that these people do not represent the general public. How accurate is that data now?

Data is essential to making critical decisions but it needs to be based on good gathering practices. Note that I did not say pristine. You can make good decisions with less than pristine data as long as you understand the limitations.

If I’m doing temperature measurements in the Texas summer, I won’t have accurate data if my probe is in the shade. Or will I? I can make a few measurements to determine the difference between the shade and bright sun at different times of the day and I can apply this factor to my overall measurements. It’s not as accurate as making the measurements in bright sun but if my probe can’t tolerate long exposure to the sun, it might be accurate enough. Here I know how the data was taken, I know how the calibration factor was arrived at and how it was applied. I could almost trust this data.

I don’t need to warn you about the dangers of relying on the imaginary data our politicians are so fond of quoting. That seems obvious enough, just look at some of their mandates. Follow the data is only a catch phrase to justify their opinion.

Ever hear about green ketchup? This week I’m listening to How Color Affects You, What Science Reveals and it gives a great example on the dangers of using data without understanding it. Green ketchup was a big hit. Parents bought it because green is still associated with tomatoes. Children loved it because its introduction coincided with Shriek. Sales boomed.

The researchers missed these factors and decided children loved bright colors in their food. Do I have to tell you what happened when they introduced blue ketchup?

Data also has a time element. Think about my tomato example or take my personal peeve, Amazon. Based on my purchases and browsing history, Amazon has almost enough information and computing power to create a digital analog of me right down to my cluttered desk. Yet when I buy a laptop with them, every website I visit for the next 15 days bombards me with ads for the same laptop or similar products. They would get far more sales if they used the data to suggest carrying cases, memory expansion kits or software. Amazon, I already have the laptop.

Even with reliable data, you need a way to view the data. For that you will probably turn to a spreadsheet. Personally, I like spreadsheets but you need to understand how the data is conditioned before relying on it. If you want some real horror stories read Humble Pi, When Math Goes Wrong in the Real World to see some of the disasters caused by people relying a little too much on their spreadsheet. You’ll never take your spreadsheet for granted again. Trust me, that’s a good thing.

If you want to say you’re relying on the data, you need to be able to explain how the data was taken, when it was taken and what it represents. Otherwise, all you’re doing is using a popular catch phrase to justify your decisions. I get it, some decisions will be unpopular with people but don’t try to justify it with follow the data.

© 2021, Byron Seastrunk. All rights reserved.