If, like me, you read a lot of reviews before making a purchase you wonder why a lot of big name companies are sending out shoddy merchandise. Sure it looks like the majority of people are completely satisfied with the product but there’s always a few dead on arrival or dead within a few weeks. These negative reviews make you wonder if the manufacturers are testing their product before sending it out.

Actually they probably test it several times but probability is against them. Electronic parts will fail, period. How soon they fail is a function of the device, the manufacturer, the operating temperature of the part and how hard it’s stressed.

Actually they probably test it several times but probability is against them. Electronic parts will fail, period. How soon they fail is a function of the device, the manufacturer, the operating temperature of the part and how hard it’s stressed.

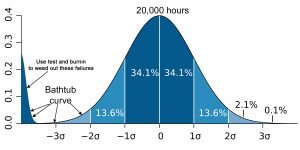

These factors are used to calculate the failure rate for this part. The sum of the failure rates for each part becomes a predicted time before a failure occurs to the assembly. This is called the mean time before failure (MTBF). As the term suggests, it’s only a guess as to when a part will fail on your nice new smart phone. This number is important to the manufacturer when he calculates his warranty exposure. You have understand this number only has meaning when you look at a large sample of these phones.

As an average, it does not mean that your particular phone will last that long before failing. Your phone could be an outlier and last twenty years or only five minutes. Modern manufacturing techniques attempts to remove early failures by stressing the phone before shipping it. Depending on the level of stress this is called burn-in, environmental stress screening (ESS), highly accelerated stress screening (HASS) or several other acronyms. All to ensure your phone arrives in working order and you don’t give negative reviews.

Here’s where a basic misunderstanding of failure rates starts to occur. If these processes aren’t resulting in failures during test, they provide no benefit at all to the consumer. If fact, they are only removing life before that first failure does occur while you own the phone. Zero failures during burn in or stress screening only means the screening is not intense enough to capture these early failures.

Here’s where a basic misunderstanding of failure rates starts to occur. If these processes aren’t resulting in failures during test, they provide no benefit at all to the consumer. If fact, they are only removing life before that first failure does occur while you own the phone. Zero failures during burn in or stress screening only means the screening is not intense enough to capture these early failures.

This brings me to one of my pet peeves, undetected failures. Another popular theme in these reviews are the people returning a defective product only to receive it again with the same problem. While it could be the user having no idea how the product operates, you also see a lot of repeat failures in the reviews. This is often because the manufacturer has streamlined his testing so thoroughly that your particular failure is no longer tested for.

Now before you get incensed about a lack of testing, all this testing represents a final cost that has to be passed along to you. Streamlining testing is only prudent if they want to stay competitive. However, when the purchasing department saves two cents on a five dollar part you can bet reliability will suffer. I’m not suggesting the manufacturer go back to 100% testing every time a part changes but he does need to perform due diligence.

On a similar note, if a lot of return failures aren’t detected by testing, don’t be so sure it’s because the users aren’t reading the warnings on page three of the manual. I know that happens frequently but those types of returns frequently indicate a hole in testing. Extra testing to discover why these failures are occurring is well worth the money.

There is one final case. Sometimes the user simply doesn’t know the product nearly as well as he thinks it does. I was looking at a fuse terminal block with LEDs to indicate a blown fuse. At least three of the reviews were complaining that the block was wired incorrectly and they still had 12 volts after the fuse was blown. Of course it was, this is how the LED operates. It’s not an issue because the current from the LED is limited. There’s no risk to anything.

There is one final case. Sometimes the user simply doesn’t know the product nearly as well as he thinks it does. I was looking at a fuse terminal block with LEDs to indicate a blown fuse. At least three of the reviews were complaining that the block was wired incorrectly and they still had 12 volts after the fuse was blown. Of course it was, this is how the LED operates. It’s not an issue because the current from the LED is limited. There’s no risk to anything.

I stand corrected, there’s a big risk to the vendor’s sales simply because people think they understand and are giving negative reviews. You would think after a few bad reviews the vendor would add an explanation to the description. Then again, maybe the vendor doesn’t understand the issue either.

Sort of puts a whole new light on all those negative reviews doesn’t it.

© 2019, Byron Seastrunk. All rights reserved.

Remember that customers with a failed product are more likely to leave a review too (usually a bad one), so when looking at bad reviews, all the people who received a perfect product and didn’t leave a review are missing from the picture. So don’t let a few bad reviews turn you away if there aren’t really that many. I know that when a product fails on me I really want to leave a bad review warning the next guy, but Amazon doesn’t let me participate in their community so that never happens.