Every decision an engineer makes goes through a risk reward analysis, each and every one. It’s not a complicated process, it doesn’t involve calculus but it’s not always obvious. Let me give you an example.

Recently my two year old Samsung dryer decided to stop working. Power would come on but the drum wasn’t turning. My first consideration probably should have involved warranty but waiting a week on a repairman, being at home at his convenience and getting him past three Australian shepherds made that question moot and I went straight to analysis.

Truthfully that last paragraph is just an excuse I give my wife. If something fails, I will open it to see if I can fix it. Once it comes into my possession, the warranty may as well be void.

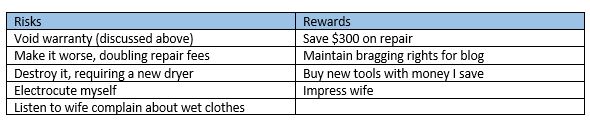

My risk reward analysis looks something like this:

I could bore you with a detailed description of my engineering acumen in fixing the dryer, I already wrote that section but after my wife read it she demanded fifteen minutes of me cleaning the kitchen to make up for wasting her time. So, two YouTube videos later and $15 dollars in parts, I had replaced an idler pulley designed to wear out.

I could bore you with a detailed description of my engineering acumen in fixing the dryer, I already wrote that section but after my wife read it she demanded fifteen minutes of me cleaning the kitchen to make up for wasting her time. So, two YouTube videos later and $15 dollars in parts, I had replaced an idler pulley designed to wear out.

I maintained my bragging rights for two whole weeks until my wife came and said the dryer broke again. Add one more risk to my analysis, once you fix something, everything else that goes wrong is a result of your repair. This time it was the heating coil, totally unrelated but not something I could convince my wife on. Another YouTube video and $20 more to repair.

My point is that everything I do goes through a risk reward analysis. Nor do I believe this is limited to engineers. “Fire hot, fire burn,” is a risk reward analysis we all learn at an early age. I do believe we engineers are more consistent about it and tend to do a deeper analysis.

What does that mean to you? If you’ve read this far, you’re probably involved with an engineer in some form or fashion. When it comes to motivating your engineer, you now understand you have to manipulate his analysis. As an engineer, we already know that once we show any sign of competence, we’re marked for life. “Oh, you knew how to fix a dryer, a washing machine should be easy.” We already know that we will only get credit for the repair one time, after that it’s always our fault.

Armed with this knowledge, how do you persuade us to tackle any task that displays competence? The engineer’s code of conduct forbids me from revealing any secrets that would allow manipulation of our psyche. I can only tell you that no true engineer would ever walk away from a challenging problem or free food.

Your choice how you use this knowledge.

What happened to my dryer:

Idler pulley with friction bearing

Okay. despite my wife’s opinion, I decided to add the explanation anyway.

I have to say Samsung did a remarkable job in designing my dryer. Assuming the goal was to last through the warranty period and start failing. The idler pulley is mounted on a solid, unsealed bearing. A little wear, a little dust and the bearing will build up enough friction to melt the inner hub of the pulley. When the dryer stops, the melted nylon flows into the bearing making the next time even worse. Sooner or later, something gives and the pulley comes off the bracket.

After ordering the part from Amazon, I was able to get another week out of the dryer by lubricating the bearing and using Gorilla glue to re-attach the nylon pulley to the bearing. I was fortunate that the replacement part arrived in time because my fix was already starting to fail.

Having the heater coil burn out two weeks later only illustrated how incredibly accurate Samsung was in their reliability predictions. Check out my post on reliability and warranty.

Having the heater coil burn out two weeks later only illustrated how incredibly accurate Samsung was in their reliability predictions. Check out my post on reliability and warranty.

© 2017 – 2019, Byron Seastrunk. All rights reserved.